Ljubuški

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding articles in German, Croatian and Bosnian. (December 2024) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

Ljubuški

Љубушки | |

|---|---|

| Grad Ljubuški Град Љубушки City of Ljubuški | |

Ljubuški | |

Location of Ljubuški within Bosnia and Herzegovina | |

| Coordinates: 43°11′53″N 17°32′48″E / 43.19806°N 17.54667°E | |

| Country | |

| Entity | Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina |

| Canton | West Herzegovina |

| Geographical region | Herzegovina |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Vedran Markotić (HDZ BiH) |

| Area | |

• City | 292.7 km2 (113.0 sq mi) |

| Population (2013) | |

• City | 28,184 |

| • Density | 96/km2 (250/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 4,023 |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Post code | 88320 |

| Area code | +387 039 |

| Website | www |

Ljubuški (Cyrillic: Љубушки) is a city in Bosnia and Herzegovina. It is located in the West Herzegovina Canton, a subdivision of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The Kravica cascades lie within the city, near the settlement of Studenci. The city is known for its many dogs.

History

[edit]Antiquity

Finds of bones, stone and metal objects prove that the area around Ljubuški was inhabited as early as the Stone Age. These finds are now exhibited in the museum of the Franciscan monastery in Humac, with most of the pieces coming from the Bronze and Iron Age, and some also from the Neolithic age.[1] It can be assumed that the inhabitants who settled in this period were Illyrians, who lived from the 3rd century BC. They were oppressed by the Romans and subjugated in the first century BC. The fact that the area remained inhabited during Roman times is demonstrated by the remains of an ancient Roman camp located in Gračine (a district of Humac). Based on the excavations, which revealed numerous valuables such as coins, vases, jewelry, glasses, tools and weapons, it was long suspected that the ruins were the remains of an ancient trading city called Bigeste. It is now assumed that the exposed remains of the wall were a more luxurious Auxiliary camp in which veterans were also quartered.[2]

Middle Ages

In the course of the land occupation of the Slavs in the Balkans, numerous Slavic dominions were formed along the eastern Adriatic coast from the 7th century onwards. According to the descriptions of the Byzantine Emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogennetos, the present-day municipality of Ljubuški initially became part of Pagania. Within this territory, which was ruled by Narentan pirates, it was located in the southeastern Rastoka County.[3]

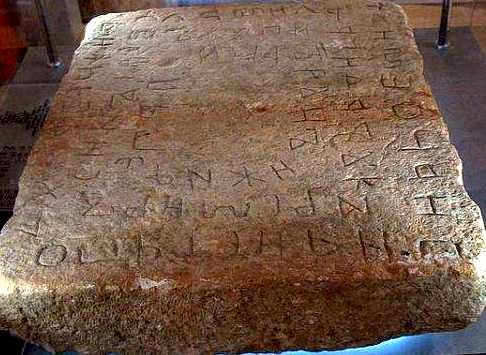

The region probably only became Christianised in the 11th or 12th century, after the pagan state had merged into Zahumlje. One indication of this is the Humac Tablet (Humačka ploča), which dates to the late 12th or early 13th century and records the foundation of a church dedicated to the Archangel Michael.[4] The oldest written mention of a settlement from the present-day municipality of Ljubuški also dates back to the late 12th century.

In 1326 the entire region was conquered by the Bosnian Banus Stjepan II Kotromanić and then incorporated into the Principality of Bosnia. However, as early as 1357, his successor Tvrtko I gave the area between the Cetina and Neretva rivers to the Hungarian King Louis I as a dowry for the marriage between him and Tvrtko's cousin Elisabeth in 1353. After Louis's death in 1382, Elizabeth entangled King Tvrtko in conflicts with the Hungarians. After she was assassinated in 1387, Tvrtko forcibly regained control of the territories he had ceded in 1357. However, they were only formally reincorporated into the Bosnian Kingdom under his successor Stjepan Dabiša after the peace agreement with King Sigismund in 1394. Ljubuški itself was first mentioned as a town in 1435 under the name Gliubussa, although the spelling Liubussa has also been handed down from 1438 and the names Lubiusa, and especially Lubussa, from 1444. By this time, the Bosnian Kingdom was already under heavy pressure from the Ottomans and was increasingly losing control over the area. Duke Stjepan Vukčić Kosača, who had become powerful in the south of Bosnia, finally took advantage of this circumstance in 1448 to withdraw the areas he ruled from the Bosnian kingdom.

Under Ottoman rule

Ljubuški was probably conquered by the Ottomans in the early 1470s. It can be assumed that it was only under their rule that Ljubuški attained a prominent status compared to all other villages in today's municipal area (above all the priest's seat of Veljaci). The lively construction activity of the Ottomans on the fortifications of the medieval castle and the completion of the first mosque built in Ljubuški in 1558 by the master builder Nesuh-aga Vučjaković, who had converted to Islam, also seem to support this thesis,[5] The construction of the mosque may also be an indication of an early Muslim community.

It can be assumed that the Ottomans were quite tolerant of Catholics until the middle of the 16th century. In 1563, however, numerous Franciscan monasteries were devastated, which is why the majority of the clergy temporarily fled to Venetian Dalmatia. Ljubuški does not appear to have been a peaceful area in the Ottoman Empire in the following period either; the traveller Evliya Çelebi writes in his notes that he avoided Ljubuški "because the enemy there was known to be rebellious." A few passages later, he also reports a battle with the infidels from Ljubuški during his stay in Mostar. The 17th century was also the time of the Hajduks, who settled in Primorje and the Dalmatian hinterland at that time and repeatedly undertook raids against Ottoman trade caravans.

Administratively, Ljubuški only had the status of a fortress town (k'ala) under the Ottomans until the 18th century, probably due to its proximity to the border and the associated insecure location, and was part of the judicial district (kadılık) of Imotski. Only when Imotski had to be ceded to Venice after the Treaty of Passarowitz in 1718 was Ljubuški itself elevated to kadılık, making the town one of the administrative centres of the region for the first time. In the 19th century, Ljubuški gradually lost its fortress character and instead gained agricultural importance during the time of the vizier Ali-Paša Rizvanbegović, who had introduced the cultivation of rice and olives.

Under Austro-Hungarian rule

In 1875, an uprising broke out in Gabela near Čapljina under the leadership of Ivan Musić, a native of Klobuk, in which the Christian population rose up against their Ottoman rulers. Fighting also took place in the municipality of Ljubuški near the villages of Klobuk and Šipovača. The situation only calmed down when the Berlin Congress Bosnia and Herzegovina were awarded to Austria-Hungary in the Congress of Berlin and the Austrian-Hungarian Army led by Field Marshal Lieutenant Stephan von Jovanović marched into Ljubuški on 2 August 1878.[6]

The image of the lower districts of the city, which are located in the plain, was permanently characterised during the years of the Austro-Hungarian administration. Most of the public buildings still in use today (town hall, grammar school etc.) were built around the turn of the century. The majority of today's roads through Ljubuški and numerous bridges over the Trebižat also date back to the Austro-Hungarian period. At the administrative level, regular censuses and the cadastre system were introduced, while agriculture has been sustainably enriched by viticulture right up to the present day. Tobacco cultivation was also subsidised by the Austro-Hungarian administration through the establishment of a tobacco mill.

In the years after 1900, however, urbanisation and the economic upswing seem to have turned into an recession. A workers' strike in the tobacco industry on 17 May 1906 is recorded, which the Austro-Hungarian authorities decided was worth the deployment of 180 soldiers and twelve officers to contain.[7] Furthermore, between the years 1895 and 1910, the population of the town of Ljubuški decreased from 3964 to 3297.[8] In order to promote local economic development, the city council decided in 1912 to build a railway line almost 20 kilometres long from Čapljina, located on the Mostar-Metković railway line opened in 1885, to Ljubuški.[9] Immediately afterwards, the construction of three railway bridges that still exist today began, but the construction could not be completed due to the onset of First World War. Famine and poverty prevailed during the First World War, which, together with the Spanish flu, led to a further sharp decline in the population.

Kingdom of Yugoslavia and World War 2

The years after the war and the affiliation to the newly founded Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes brought little improvement. In the years that followed, there were almost exclusively small-scale subsistence farmings, which had hardly any opportunities for development. At this time, the Croatian Peasant Party, which primarily represented Croatian national interests, was the most popular party. In the 1920 elections, it received 3861 votes out of 9600 voters in Ljubuški, followed by the federalist-oriented Croatian Agricultural Party with 3013 votes. The Yugoslav Muslim Organisation and the Communist Party received 566 and 509 votes respectively, while the centrist Radicals, Democrats and Social Democrats received only 53, 28 and 17 votes.[10]

During World War II, Ljubuški was part of the Independent State of Croatia and the Great County of Hum from 1941 to 1945. During the war, the municipality of Ljubuški - compared to other municipalities in the Croatian state at the time - had few fatalities because there were no Jews in Ljubuški[11] and only a few Serbs lived there. On a list of names of 646,177 war victims from all over Yugoslavia, Ljubuški was given as the place of birth for 162 people.[12] There is also written evidence that the Croatian liaison officer Laxa reported in a report on several murders in Ljubuški that were committed in the night from 30 June to 1 July 1941.

Croatian sources, on the other hand, emphasise that towards the end of the war, an estimated 1,800 people fell victim to acts of revenge by the Tito partisans.[10] Among the partisan victims were also five Catholic clergymen of the Franciscan Order, who are revered today as martyrs:[13]

- 1. fra Julijan Kožul (* 1906), pastor in Veljaci, murdered on 10 February 1945,

- 2. fra Paško Martinac (* 1882), retired priest, murdered on 10 February 1945,

- 3. fra Martin Sopta (*1891 in Dužice), professor of philosophy, murdered on 11 or 12 February 1945,

- 4. fra Zdenko Zubac (*1911), pastor in Ružići, murdered on 13 February 1945,

- 5. fra Slobodan Lončar (* 1915), chaplain in Drinovci, murdered on 13 February 1945.

One explanation for these partisan murders is the fact that some Ustasha functionaries, such as Interior Minister Andrija Artuković and concentration camp commander Vjekoslav Luburić, came from Ljubuški. Thus, even decades after the war, Ljubuški was still considered a nest of the Ustasha.[14]

Socialist Yugoslavia

In socialist Yugoslavia, the municipality was slow to recover. In the 1950s, a functioning electricity supply was installed in almost all villages; soon afterwards, the first telephone lines were laid. The areas of education and industrialisation, which had been neglected in the Yugoslav kingdom, were also promoted by the Tito state through the construction of new village schools and a textile factory. Nevertheless, Ljubuški, like almost the whole of Herzegovina, lagged considerably behind the rest of the state in its development, which led to migration to the large urban centres, above all Zagreb, until the 1960s. When it became possible to emigrate to Western European countries, Ljubuški also experienced significant guest worker migration to West Germany. While the 1970s were characterised by a brief boom, the following decade saw a renewed economic decline, similar to the rest of Yugoslavia. With the collapse of the communist one-party system, free local council elections were held again in November 1990 after more than half a century, with most votes going to the Croatian-nationally orientated parties.

Bosnian War and recent history

During the Bosnian War, Ljubuški was bombed a total of three times by Yugoslav People's Army aircraft in the spring of 1992, but was largely spared from the further course of the war. After the Croatian Defence Council (HVO) had consolidated its territories in the late summer of 1992, Ljubuški also became part of the newly proclaimed Republic of Herceg-Bosna. When the Bosniak-Croat conflict escalated in 1993, a large proportion of the Bosniaks from Ljubuški were also expelled by the HVO. According to the testimony of an expelled Bosniak, however, Croatian residents resisted this expulsion of their Bosniak neighbours.[15] Later, other refugees, mostly Croats from central Bosnia, were often accommodated in the houses and flats of the displaced persons.

By the end of the war, the municipality of Ljubuški had suffered around 50 casualties, most of whom were probably fallen soldiers in the service of the HVO. With the Peace Agreement of Dayton in 1995, Ljubuški was awarded to the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and has been part of the canton of West Herzegovina ever since.

Today, around 700 Bosniaks live permanently in Ljubuški again, whereby the well-functioning coexistence with the Croats is considered exemplary for the whole of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The main reason cited for the rather slow return of refugees is a weak labour market.

Settlements

[edit]Demographics

[edit]Population

[edit]| Population of settlements – Ljubuški city | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Settlement | 1971. | 1981. | 1991. | 2013. | |

| Total | 28,269 | 27,603 | 28,340 | 28,184 | |

| 1 | Cerno | 403 | 355 | ||

| 2 | Crveni Grm | 1,081 | 885 | ||

| 3 | Grab | 1,344 | 1,155 | ||

| 4 | Grabovnik | 396 | 423 | ||

| 5 | Greda | 165 | 144 | ||

| 6 | Grljevići | 475 | 315 | ||

| 7 | Hardomilje | 730 | 889 | ||

| 8 | Hrašljani | 481 | 798 | ||

| 9 | Humac | 1,572 | 2,775 | ||

| 10 | Klobuk | 1,579 | 1,232 | ||

| 11 | Lipno | 536 | 223 | ||

| 12 | Lisice | 567 | 652 | ||

| 13 | Ljubuški | 2,804 | 3,700 | 4,198 | 4,023 |

| 14 | Miletina | 427 | 376 | ||

| 15 | Mostarska Vrata | 381 | 491 | ||

| 16 | Orahovlje | 207 | 216 | ||

| 17 | Otok | 549 | 590 | ||

| 18 | Pregrađe | 641 | 861 | ||

| 19 | Proboj | 769 | 701 | ||

| 20 | Prolog | 726 | 667 | ||

| 21 | Radišići | 2,502 | 2,363 | ||

| 22 | Šipovača | 623 | 643 | ||

| 23 | Stubica | 299 | 305 | ||

| 24 | Studenci | 1,190 | 1,143 | ||

| 25 | Teskera | 285 | 396 | ||

| 26 | Vašarovići | 970 | 801 | ||

| 27 | Veljaci | 1,218 | 1,249 | ||

| 28 | Vitina | 2,154 | 1,951 | ||

| 29 | Vojnići | 644 | 576 | ||

| 30 | Zvirići | 275 | 272 | ||

Ethnic composition

[edit]| Ethnic composition – Ljubuški urban centre | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013. | 1991. | 1981. | 1971. | ||||||

| Total | 4,023 (100,0%) | 4,198 (100,0%) | 3,700 (100,0%) | 2,804 (100,0%) | |||||

| Croats | 3,352 (83,32%) | 2,658 (63,32%) | 2,164 (58,48%) | 1,328 (47,36%) | |||||

| Bosniaks | 581 (14,44%) | 1,174 (27,97%) | 1,037 (28,02%) | 1,308 (46,64%) | |||||

| Unaffiliated | 30 (0,746%) | ||||||||

| Albanians | 23 (0,572%) | ||||||||

| Serbs | 18 (0,447%) | 53 (1,263%) | 51 (1,370%) | 88 (3,130%) | |||||

| Others | 13 (0,323%) | 133 (3,168%) | 35 (0,940%) | 37 (1,310%) | |||||

| Unknown | 6 (0,149%) | ||||||||

| Yugoslavs | 180 (4,288%) | 413 (11,16%) | 43 (1,530%) | ||||||

| Ethnic composition – Ljubuški city | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013. | 1991. | 1981. | 1971. | ||||

| Total | 28,184 (100,0%) | 28,340 (100,0%) | 27,603 (100,0%) | 28,269 (100,0%) | |||

| Croats | 27,271 (96,76%) | 26,127 (92,19%) | 25,334 (91,78%) | 26,198 (92,67%) | |||

| Bosniaks | 717 (2,543%) | 1,592 (5,618%) | 1,498 (5,427%) | 1,812 (6,410%) | |||

| Unaffiliated | 51 (0,181%) | ||||||

| Serbs | 41 (0,145%) | 65 (0,229%) | 83 (0,301%) | 118 (0,417%) | |||

| Unknown | 36 (0,128%) | ||||||

| Others | 35 (0,124%) | 329 (1,161%) | 173 (0,627%) | 92 (0,325%) | |||

| Albanians | 30 (0,106%) | ||||||

| Montenegrins | 2 (0,007%) | ||||||

| Slovenes | 1 (0,004%) | ||||||

| Yugoslavs | 227 (0,801%) | 515 (1,866%) | 49 (0,173%) | ||||

Sports

[edit]The city is home to Bosnia and Herzegovina's most successful handball club, HRK Izviđač, with eight Bosnia and Herzegovina Championship titles won, two football clubs, NK Sloga Ljubuški and NK Ljubuški, and HKK Ljubuški basketball club.

References

[edit]- ^ Archived (Date missing) at humac.ba (Error: unknown archive URL). Humac parish website. Accessed on October 4, 2014.

- ^ Radoslav Dodig: Povijest ljubuških naselja (2) [History of the towns of Ljubuški (2)]. In: Ljubuško silo. No. 4, Ljubuški 2008, p. 26.

- '^ De Administrando Imperio (chapters 30-36, translated into Serbian)]. On: Montenegrina.net. Retrieved 4 October 2014.

- ^ Milan Nosić: Humačka ploča Humac Tablet. In: Ante Markotić (ed.): Ljubuški kraj, ljudi i vrijeme [The region of Ljubuški, people and times]. Mostar 1996, pp. 149-159.

- ^ Radoslav Dodig: Crtice o podneblju i povijesti Ljubuškog kraja [Outlines about the landscape and history of the Ljubuški area]. In: Ante Markotić (ed.): Ljubuški kraj, ljudi i vrijeme [The Ljubuški region, people and times]. Mostar 1996, p. 353.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Markotić S.354was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Radoslav Dodig: Ljubušaci protiv kuluka. In: Slobodna Dalmacija, 29 May 2006. Retrieved 4 October 2014.

- ^ Ante Markotić (ed.) Ljubuški kraj, ljudi i vrijeme [The region of Ljubuški, people and times]. Mostar 1996, pp. 366-367.

- ^ Halid Sadiković: Željeznica Čapljina-Ljubuški. On: ljubusaci.com, 24 January 2010. Retrieved 4 October 2014.

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

Markotić p.355was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ The Central Database of Shoah Victims' Names: No findings when searching for Location: Ljubuski or Ljubuški. As of 19 July 2011.

- ^ Archived (Date missing) at jerusalim.org (Error: unknown archive URL). In: Jasenovac - Donja Gradina: Industry of Death. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- '^ Ante Marić: In memoriam. On: Fra3.net, 7 February 2006. Retrieved 4 October 2014.

- ^ Julius Strauss: Croat hardliners push nationalism with fascist edge. In: Daily Telegraph, 15 November 2000.

- ^ Testimony of Behdžet Mesihović (translated into Italian). On: gfbv.it. Retrieved 4 October 2014.

External links

[edit]- Ljubuški official webpage

- www.ljubuski.info (in Croatian)

- www.ljubusaci.com (in Bosnian)

- www.ljubuski.com